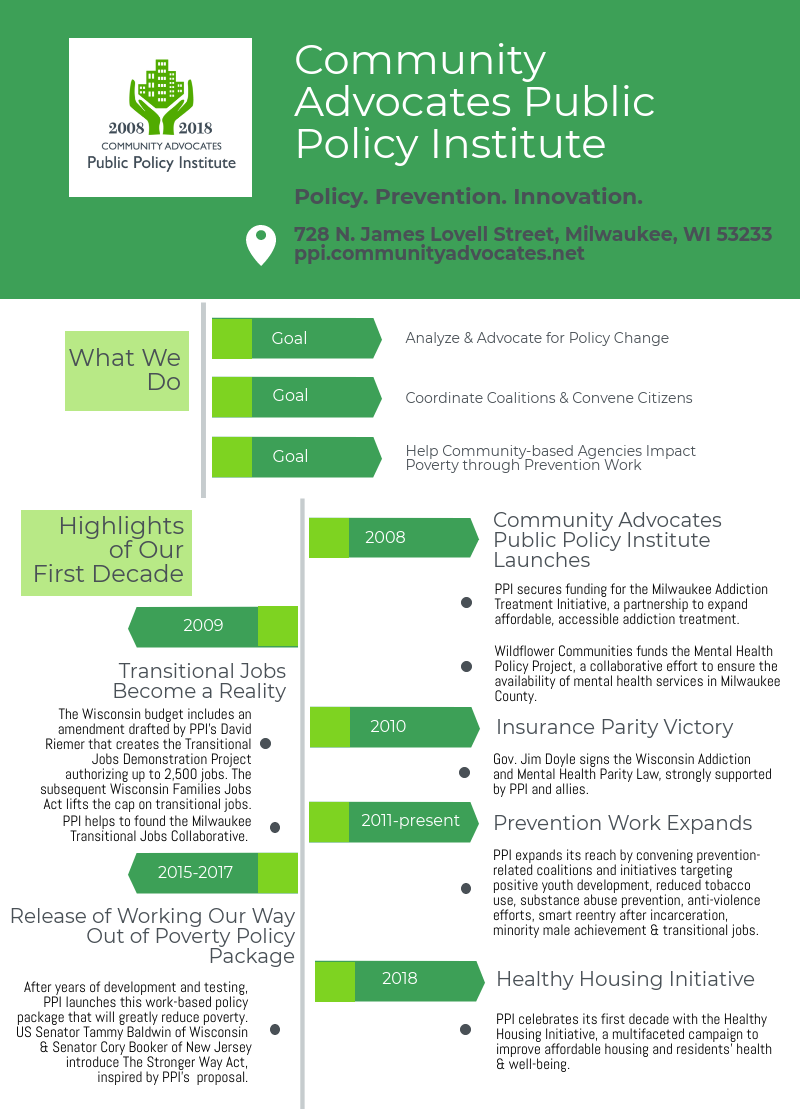

Community Advocates' leadership created the Public Policy Institute in 2008 to expand on the services the organization provides to our clients seeking help with their housing, health care, behavioral health, and safety needs. Instead of only connecting Milwaukeeans with these services, the Public Policy Institute would try to solve the root causes of what compelled our clients to seek out these services.

Community Advocates tapped David Riemer as its first director. Riemer had a long history in policy work as a researcher and member of local and state governments. He played a major role in the enactment of the state’s Earned Income Tax Credit; W-2 welfare reform; BadgerCare, the state’s version of Medicaid; and the state’s Office of the Public Defender.

“I was told that Community Advocates was interested in doing public policy in a more systematic way and would be a formal, institutional part of the organization,” Riemer said.

The institute was set up to research and propose nonpartisan policy solutions to issues connected to poverty but to do it in a way that was true to Community Advocates’ guiding spirit: by forming coalitions and seeking input from the affected community members.

“Advocacy would be part of it,” Riemer said. “It’s in our name, in our bloodstream.”

The institute got off to a promising start in 2008 by winning funding from the New York-based Open Society Institute, which was soliciting proposals to deal with addiction. The new Public Policy Institute drew on Community Advocates’ strength as a coalition builder and submitted a proposal for the Milwaukee Addiction Treatment Initiative (MATI).

“I didn’t think we had much of a chance of winning, because these things are pretty competitive,” Riemer said. “But we did have a unique angle, which was to provide addiction and mental health treatment not as a standalone effort but as part of comprehensive health insurance. Part of the reason why we got the grant was not just the concept, but because of Community Advocates’ history of being a coalition builder.”

Members included local elected officials, law enforcement, health experts, and community members, while the Greater Milwaukee Foundation, the Zilber Family Foundation, the Helen Bader Foundation (now Bader Philanthropies) and the Archdiocese of Milwaukee Supporting Fund also provided vital financial contributions.

From there, the institute won Wildflower Communities funding for the Mental Health Policy Initiative, a collaborative effort to ensure the availability of mental health services in Milwaukee County. PPI also oversaw the Tobacco Prevention and Control Program to measure compliance with the state’s new smoke-free law.

In addition to these community-based initiatives, the Institute won big successes in the Wisconsin Legislature, too. PPI was the driving force behind the Transitional Jobs Demonstration Project in the 2009 state budget, as well as the subsequent Wisconsin Families Jobs Act, which lifted the cap on Transitional Jobs, and the Mental Health Parity Law, which Gov. Jim Doyle signed in 2010.

All the while, PPI was adding prevention-related programming to its work, realizing that preventing problems from arising in the first place is more beneficial and effective than dealing with the problem once it’s taken hold.

Instead of going it alone, PPI stayed true to Community Advocates’ roots and began organizing coalitions and listening to the community. PPI-convened coalitions include the RISE Drug Free MKE coalition (formerly MCSAP), the City of Milwaukee Tobacco-Free Alliance, the 53206 Drug-Free Communities Project, the Healthy Housing Initiative, Coming Together Partnership for Prevention of Gun Violence, the Milwaukee Reentry Council, the Southeast Region of the Alliance for Wisconsin Youth, the Minority Male Achievement Program, the Teen Pregnancy Prevention Network, Youth Works MKE, the Milwaukee Transitional Jobs Collaborative, and Healthy Workers Healthy Wisconsin.

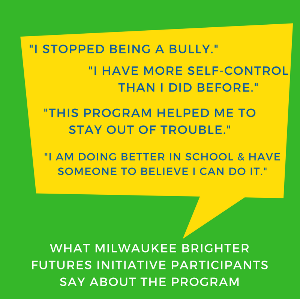

PPI also directs grants to community partners engaged in positive youth development through our Milwaukee Brighter Futures Initiative, Stay Strong Milwaukee, the Alliance for Wisconsin Youth Southeast Region, the Opioid State Targeted Response, and the Early Childhood Initiative.

To prevent and reduce child abuse and maltreatment, PPI is implementing the Stronger Families Milwaukee pilot program and the Milwaukee Family Intervention Services program.

In addition, PPI provides workshops to community members through our Mental Health Awareness Training series and the Empowerment Coalition of Milwaukee monthly gatherings.

Along with the expanded prevention portfolio, PPI’s researchers were trying to develop nonpartisan, work-based policy proposals that would have the greatest impact on low-income Wisconsinites left behind in the new economy.

“We were working on this notion of trying to figure out what it would take to greatly reduce poverty,” Riemer said.

First, they came up with a handful nonpartisan policy proposals—a tax credit for seniors and adults with disabilities, a Transitional Jobs program for unemployed job seekers, a higher minimum wage, and a reformed Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) for low-income earners—and asked the Urban Institute to test their impact in Wisconsin. The result? An astounding finding: The four-part policy package, now known as the Pathways to Ending Poverty package, would slash poverty in Wisconsin between 58% and 81%.

Later, similar proposals were tested to identify their impact outside of Wisconsin. The broader package released in 2015, Working Our Way Out of Poverty, included five elements: the creation of a Transitional Jobs program, raising the minimum wage to $10.10, reforming the EITC and eliminating the marriage penalty, strengthening child care funding, and enacting a secure retirement and disability income tax credit.

Once again PPI saw dramatic results. The Urban Institute found that Working Our Way Out of Poverty would cut poverty throughout the country by 50%, lifting more than 22 million people out of poverty.

“We were pushing this notion that a work-based strategy that involved a relatively small number of policy changes could be shown to dramatically reduce poverty wherever it was applied,” Riemer said. “That was a very major initiative. In some ways it was the most creative and most important thing we’ve done.”

PPI then reached out to Wisconsin Senator Tammy Baldwin to see if these proposals could be drafted into a legislative proposal. Baldwin was so impressed that not only did her office draft a proposal with PPI’s input, but she and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey introduced it in the US Senate as The Stronger Way Act. In October 2017, Baldwin and Booker unveiled their legislation with a press event in Community Advocates’ downtown Milwaukee offices.

Riemer was quick to acknowledge the many experts, advocates, and funders who have supported PPI in the past decade. Local, state, and federal policy-makers from both sides of the aisle, as well as local and national foundations and individuals, have played a large role in our work and our expanding reach.

In addition, Community Advocates' Board of Directors, administration, and former and current staff -- including Rob Cherry, Paula John, Debra Kraft, Melissa McGaughey, Sue Potts, and Kris Uhen -- worked tirelessly to establish PPI as a respected source of information and advocacy on issues related to reducing poverty, violence, and substance abuse.

"We are so grateful to all who have contributed to PPI's mission to prevent poverty and increase the health, self-sufficiency, and wellbeing of our vulnerable friends and neighbors," said PPI Deputy Director Kari Lerch. "We're looking forward to building on our achievements in our next decade."