Addressing Childhood Lead Poisoning Prevention in Milwaukee

Geoffrey R. Swain, MD, MPH

Childhood lead poisoning is far too common in Milwaukee, and it has powerfully negative lifetime effects on health. Describing “what needs to be done” to prevent childhood lead exposures is relatively simple, but doing what needs to be done is not easy.

It’s not easy in large part because of key tensions related to the huge costs involved, to prioritizing lead-in-paint vs lead-in-water, to focusing on rental units vs owner-occupied units, and to prioritizing primary prevention (before lead poisoning occurs) vs secondary prevention (after a child already has elevated blood lead levels).

These tensions, however, can be managed, as described below. We should not let arguments over smaller details keep us from the bigger picture: There is a path forward to prevent Milwaukee kids from getting lead poisoned. We all need to step up and assure that key financial investments and policy changes are made so that all Milwaukee kids can have a safe, healthy, and lead-free future.

Huge Financial Investments Now vs Even Larger Costs Later

Mitigating all the lead hazards in the City of Milwaukee would take an investment of between $1.3 billion and $1.9 billion:

- Roughly $700 million to get rid of all of Milwaukee’s estimated 70,000 lead-based water service lines at a cost of about $10,000 per service line (this does not include lead hazards in interior plumbing, including certain fixtures and lead-containing solder)

- Between about $600 million and $1.2 billion to mitigate existing hazards related to lead-based paint; there are about 120,000 units with lead-based paint hazards that either need window replacement (about $5,000 per home) or need all paint hazards addressed in the home (about $10,000 per home)

As large as this price tag is, the costs of failing to act are staggering. Every $1 that is not invested in lead hazard control now results in $17-$221 of downstream costs, ranging from medical costs to learning disabilities to behavioral and criminal justice expenditures, according to a 2019 study.(1)

Hazards Related to Paint vs Hazards Related to Water

Since the lead-in-water disaster in Flint, Michigan, significant attention has been paid to lead hazards in water. Pipes, fixtures, and solder containing lead all can contribute to lead ingestion from water, particularly for bottle-fed babies (and the younger the child, the greater risk for adverse neurodevelopmental effects from lead exposure). Portions of water infrastructure – lead service lines in particular – are clearly a governmental responsibility. And once lead-containing water infrastructure has been replaced, it will never cause lead exposure again (as opposed to paint, which may need ongoing maintenance and remediation over time).

On the other hand, consensus from multiple nationwide studies, as well as supporting evidence from Milwaukee specifically, strongly indicates that, on average, dust and paint chips from deteriorating lead-based paint are much more powerful drivers of population-level increases in childhood blood lead levels than lead from waterborne sources. Most of the significant reductions in Milwaukee kids’ blood lead levels in the 10-20 years prior to 2016 (which is when water became more of a focus) can be primarily attributed to mitigation of paint-related lead hazards.

Moreover, while replacing lead service lines is relatively straightforward, most housing units with lead service lines are at high risk for having lead-containing indoor plumbing, including leaded solder and lead-containing faucets and other fixtures. Those housing units would still need to use a lead-removing water filter, even after replacing the lead service line. Therefore, funding for broad filter availability makes more sense than prioritizing lead service line removal at the expense of either filter distribution or paint hazard remediation.

Primary Prevention vs Secondary Prevention

Should we prioritize lead remediation projects in housing units where no children currently have elevated blood lead levels (primary prevention), or should we prioritize lead mitigation in homes where children already show signs of exposure (secondary prevention)?

On one hand, it is unethical and intolerable to “use kids as lead-hazard detectors” -- which is how some people characterize the current practice of focusing available resources to identify and mitigate lead hazards in homes where kids already have elevated blood lead levels.

But it is probably at least as unethical and intolerable to divert resources away from kids with elevated lead blood levels to try to mitigate hazards in housing units where kids don’t live now (and might or might not live in the future), or even to mitigate hazards in housing units where kids already live but don’t have elevated blood lead.

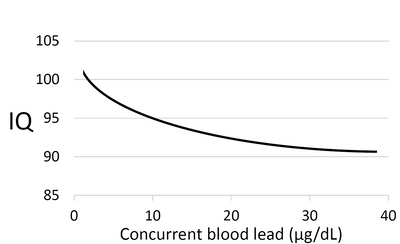

Moreover, while it’s true that the most rapid decline in neurodevelopment occurs at the lowest blood lead levels (see graph at right), it is also true that additional IQ decline continues as levels get higher. Therefore, it’s probably also unethical to divert resources away from kids with higher blood lead levels in order to focus on kids with only slightly elevated blood lead.(2)

It’s also important to remember that mitigating lead hazards in a housing unit which currently has a kid with an elevated blood lead level also serves to protect kids who will live in that housing unit in the future. So, secondary prevention of environmental lead hazards is simultaneously primary prevention. In other words, it helps existing lead-poisoned kids now, and it prevents future kids living there from lead exposure in the first place. This is particularly true in Milwaukee, where renters move frequently from one housing unit to another.

Homeowners vs Renters

While no child should be exposed to lead hazards, most children in the City of Milwaukee live in rental housing, and renters have less capacity to effect change in their housing than owners do. Therefore, while owner-occupied units should not be ignored, they should not be overemphasized. It’s important to place the priority of publicly funded interventions on where lead-exposed children live (which, in Milwaukee, is primarily in rental units).

How Should We Move Forward?

In my view, we need to do a few key things simultaneously:

Put policies and systems in place to assure that ALL kids in Milwaukee get blood lead testing at ages 12 months, 18 months, and 24 months at a minimum (and more testing in specific situations). Right now, we’re missing too many kids: kids who haven’t gotten enough testing, and many who haven’t had any testing.

Starting with the kids who have the highest blood lead levels, target the bulk of existing resources at mitigating environmental lead hazards for as many kids with elevated blood lead levels as possible. In other words, the blood lead level threshold for lead hazard mitigation should be set at the lowest level possible in proportion to the available mitigation funds.

Set aside a minority proportion of available lead hazard mitigation funds to support longer-range, solely primary-prevention efforts. For example,

- Paying for accurate and accessible lead-hazard education

- Paying for broad water filter availability

- Paying to replace all lead water pipes within an aggressive but feasible timeframe (e.g., 50 years). The city must coordinate this plan with property owners, since it involves both city-owned and privately owned infrastructure

- Requiring lead-hazard inspections of rental properties – at a minimum lead dust testing

The proportion of funds set aside for these purposes is a judgment call; in my view probably no more than 10% of the total should be earmarked for longer-range, solely primary-prevention efforts, in order not to excessively short-change the many kids with existing elevated blood lead levels.

Pass a policy that requires lead inspections of rental properties, and requires mitigation if hazards are found.

- Funding must be identified to support required inspections and for needed mitigation -- funding that doesn’t cut into money needed for units with lead-poisoned kids already in them. For example, loan funds that landlords pay back over time that can subsequently be re-loaned to other landlords

- A “phase-in” option might include starting the requirement with larger units, or “larger landlords” who presumably will be better positioned to pay for it themselves

Partner with funders, philanthropies, etc., to identify and commit as much as possible of the needed ~$1-2 billion that could get us where we really need to be.

- The large bulk of these additional funds should go to mitigate hazards where kids with existing elevated blood lead levels live – this is combined secondary and primary prevention – and a small, but not insignificant, portion should go to solely primary-prevention efforts

- Consider using available public funds to leverage significant additional private equity to invest in lead hazard remediation, such as has been done in Detroit, Newark, Kansas City, and other places

As we continue to make progress, there will be fewer and fewer kids with very high levels, and we can focus more and more on kids with lower and lower levels, until no child has any elevated blood lead level in Milwaukee.

Conclusion

Describing what needs to be done to prevent childhood lead exposures remains relatively simple. While doing what needs to be done is admittedly not easy, we should not let arguments over smaller details keep us from the bigger picture: We all need to step up and assure that significant financial investments and key policy changes are made so that all Milwaukee kids – and Milwaukee communities – can have a safe, healthy, and lead-free future.

Dr. Swain is a board-certified family physician. Prior to his recent retirement, he served for 26 years as medical director for the City of Milwaukee Health Department, and served as a faculty member at both the Medical College of Wisconsin and the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health.

Footnotes:

(1) E Gould, Environ Health Perspect. 2009 Jul; 117(7): 1162–1167: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2717145/

(2) Graph is approximated from Lanphear et al, Environ Health Perspect. 2005 Jul; 113(7): 894–899; available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1257652/